History of the Burlington Waterfront

|

|

|

|

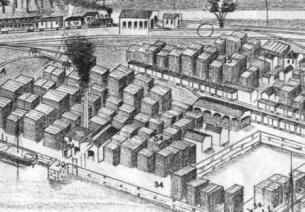

In the mid-1800s, Burlington was the third largest lumber port in the country. The 1800’s waterfront was an incredibly active and lively place and the economic driver of the City. Engravings from the period show a waterfront where every available space was used for lumber storage, rail siding, and other commercial activities.

To support these activities, the shoreline of the Burlington waterfront (once a long, sandy crescent) was repeatedly filled and expanded: a process that would go on into the 1950s. Thousands of yards of fill from the City’s hillside, railway construction, and other unknown locations, were placed into the lake behind timber and rock cribbings to create new acreage. This expansion of Burlington's waterfront was allowed for through the state-mandated “Public Trust Doctrine”: a determination that these new lands would become a direct public benefit. At that time, the expansion of waterfront land was critical to the livelihood of most Burlingtonians and was accepted as justifiable under Public Trust. Under the Public Trust Doctrine, over 60 acres of the new land area were created (roughly from the current bike path west), on which millions of board feet of lumber were processed and shipped, thousands of trainloads and barge shipments processed, and hundreds of people worked and lived.

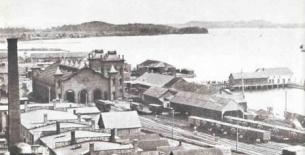

The lumber industry began to decline in the early 1900's, and profound changes began to occur on the waterfront. Early 20th century drawings show a large increase in rail tracks and infrastructure during the expansion of rail’s dominance in freight and travel. The rail yard was beginning to subsume the filled “Public Trust” lands, changing the landscape and use patterns significantly.

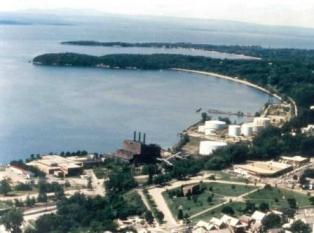

In the early and mid-20th century, with rail in decline, the waterfront moved with the times again, evolving into a bulk petroleum facility. Gasoline, diesel, JP4 jet fuel, and fuel oil was shipped to the local market in large transport barges through the Hudson River/Champlain Canal system. Millions of gallons of fuel were being shipped by water annually until the early 1990’s when trucking and rail became a more cost-efficient means of transport. At its peak, huge above ground storage tanks lined most of the shoreline from Oakledge to North Beach. At one time, there were 83 above ground bulk storage tanks on the Burlington waterfront.

In recent years, barge traffic has ceased on the lake, a result of navigational difficulties (siltation in the south lake) and a shift in petroleum to transport to rail and truck. While most of the bulk tanks are gone, the vestiges of the barge era (oil bollards in the harbor, residual soil and groundwater contamination, subsurface equipment and piping) still remain.

By the end of the 1980s, the filled lands of the waterfront had fallen into decay. Petroleum shipments by barge were being phased out, rail was in decline, and conditions of remaining equipment and buildings were poor. The Moran Generating Plant was decommissioned in 1986, leaving additional impacted acreage and a vacant industrial building. By the mid-1980s, the majority of the north waterfront was completely inaccessible: locked gates and barbed wire surrounded bulk petroleum tanks, scrap metal, old rail siding, abandoned rail cars, and rubble.

Vermont Railway, then the owner of the Urban Reserve and Waterfront Park, was managing a series of leases for petroleum storage, many of which were being canceled. Conditions in the north waterfront were worsening, soils were stained with petroleum, equipment was beginning to rust away, and there were no apparent solutions being offered for cleanup and re-use.

The City of Burlington took action in the late 1980s. With the leadership of then-Mayor Bernie Sanders and CEDO Director Peter Clavelle, the City used the Public Trust Doctrine in court as a means to re-claim the filled lands of the waterfront for public use. In a historic Supreme Court ruling, the lands were all deemed to be “impressed by the Public Trust Doctrine”, further ruling that the petroleum storage and rail siding were no longer uses beneficial to the general public. The Court directed the Vermont Legislature to create a list of acceptable uses of Public Trust Lands based on the findings of the ruling. The State legislature then defined Public Trust Lands as those reserved for "indoor or outdoor parks and recreation uses and facilities including parks and open space, marinas open to the public on a non-discriminatory basis, water-dependent uses, boating, and related services." The filled lands of the waterfront were to be transformed forever, with a focus on public access and enjoyment.

Subsequent to the Supreme Court ruling, the City was able to acquire over 60 acres of waterfront lands from Vermont Railway, but in turn, took on the responsibility for cleanup of the properties. A conservation easement was placed on the land for 50% of the acreage, along with restrictions for use within a 100-foot shoreline buffer strip. A rare species were identified on the eastern hillside, now protected by the easement. This was the beginning of the current effort to “re-naturalize” lands that were all man-made and impacted by a series of industrial uses over a 150-year period.

Planning for the future, the City divided the Public Trust acquisition into segments, after first receiving permission from the State Legislature which has continuing authority over the Public Trust Doctrine. The area south of the Coast Guard would be developed into Waterfront Park, completed in 1991. The Moran Plant, Depot Street, and Water Department complex was designated as an “Interim Development Area” allowing for the development of public amenities allowed under Public Trust.

Most compelling was the decision to leave the remaining 40-acre Urban Reserve (also known as the "North 40," from Moran to North Beach) for "future generations" to decide on its use. This intentional delay in planning for the Urban Reserve has had a profound effect. In the past few years, the site has undergone significant cleanup and has rebounded with natural vegetative cover. Thousands have "discovered" the property, are using it regularly, and are adopting their own ideas about the future of the site.

In 1988, the City constructed the Burlington Community Boathouse. At the time, it was the only true waterside public access on the north waterfront. Meanwhile, the last of the large, above ground bulk petroleum tanks were being removed north of the Moran Plant. The City then constructed Waterfront Park and Promenade at the bottom of College Street in 1991, after placing a cover of clean earthen fill over soils impacted by past petroleum-related uses, creating a new shoreline and raised boardwalk to protect the riparian strip.

In 1999, the City removed 800 yards of macadam from under Lake Street, which was being rebuilt. Macadam is a combination of oil and gravel, which were combined in the past to make roadways. The macadam was stockpiled, then placed into “windows,” naturally remediated until the petroleum compounds were benign, and placed into the subsurface with a clean fill cover.

In 1998 and 1999, the City placed clean fill at what is now the Waterfront Dog Park, with Vermont DEC pre-approval. The fill provides separation between petroleum hydrocarbons in the soils and people using the site. It allows for the compounds to naturally break down over time, additionally aided by the roots of plants now growing in the soils. The dog park now provides a location where owners clean up after their animals and have been a success at significantly reducing the amount of dog waste on the waterfront, a major contributor to water quality degradation.

In 1999 and 2000, the City focused on the so-called “Astroline Site”, a 3-acre site on the Urban Reserve which was the main distribution point for petroleum. Using a combination of capital and Waterfront Bond monies, the City demolished three buildings, decommissioned the pump house, removed a subsurface oil-water separator, and disposed of asbestos, lead, and other hazardous wastes left in the buildings.

From 2000-2003, the City worked with the Senator Leahy’s office, the US Army Corps of Engineers and Coast Guard to rebuild the Burlington breakwater and create historic replica lighthouses. These projects were staged at the Astroline site, which offers both landside and waterside access. Using lease income (for staging the breakwater and lighthouse projects), services donated by contractors, and an equipment barter with the City of South Burlington, the City was able to conduct additional cleanup activities, remove significant amounts of concrete and asphalt, repair the seawall, remove a large steel walkway, and place 18’ of clean fill over the Astroline site at no cost to the taxpayers.

Contractors also located an old car and other large objects on the harbor floor and removed them for disposal. The lease income was also used to remove the old Pease Grain Tower foundation and re-grade the site. Seeding of the Astroline site was scheduled for 2005, but the site rebounded with natural cover, as did the dog park area several years earlier.

From the outset of the Urban Reserve cleanup process, it became clear that a study of the harbor bottom should be completed, both from an environmental standpoint and to locate cultural resources (shipwrecks, old pilings, etc.) to document and assess their condition. The City worked with Senator Leahy's office to secure funding through the US Army Corps, and the Underwater Cultural Resources Survey was completed in 2006. A team from the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum used side-scan sonar, underwater photography, and GPS techniques to create a comprehensive inventory and map of the harbor bottom, locate rubble, submerged cribs, siltation and stormwater problems. They also performed historic preservation "clearances" for work on removing oil bollards, ensuring that the removal of these structures does not have a negative impact on cultural resources.

In 2000, the City constructed a Skate Park in an area formerly used for scrap metal storage. Data from the Urban Reserve Phase II ESA was crucial in helping Vermont DEC provide clearance for construction, specifying how the top layer of soils was to be managed, and ensuring that there were no public health or safety issues. Planning is currently underway for resisting the Skate Park in connection with the redevelopment of the Moran Plant.

In 2003, ECHO Lake Aquarium and Science Center, at the Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, opened at the site of the former Naval Reserve building next to the Boathouse. Significant asbestos and lead paint issues were abated during demolition, and a completely new, LEED-rated building was constructed. ECHO, a hybrid museum of history, environment, and culture, has emerged as a huge community resource and internationally known destination point.

In 2004, the Burlington Community Land Trust in partnership with other housing organizations constructed Waterfront Housing, a LEED-rated affordable housing project. Using data from the Phase II ESA, developers ensured that there was no migration of contaminants, and constructed a foundation that avoids any contact with impacted soils. Significant stormwater improvements were made on Depot Street and at the housing site, and significant geotechnical issues were resolved on the hillside.

In 2006, the Lake Champlain Basin Program/US Army Corps of Engineers Partnership Program selected the College Street Stormdrain project for support, with fall 2007 construction. This work mitigated the water quality issues created during storm events when stormwater from catch basins located as far away as upper Pine Street emptied directly into the harbor.

More recently, transportation improvements have been undertaken and the redevelopment of the Moran Plant is underway.